- Gabriel Ndayishimiye

- Jul 17

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 19

To: Mrs. Margaret Whitely, The Inspector, The Boss

Subject: On My Readiness to Resign

Date: March 5, 2025

Madam,

I suppose it is customary, when a man resigns, to thank his superior for the opportunity, to explain himself politely, to leave the door open, so to speak. But what is there to explain? I have nothing polite to say, and the only door I see is the one I should have walked through the day I started here.

You inspected the floor yesterday and found it wanting. Fair enough, so did I. You spoke to me as one speaks to a child, though you and I both know I am no child. In fact, I know you knew it too, because when you saw me hesitate, cornered, your eyes glimmered with a little satisfaction. That is how it is, is it not? You live for that moment when a man, however slightly, lowers his eyes before you.

So I told you I was ready to resign. And later, yes, I said the most ridiculous thing I could have said: “You know I am educated.” And you smirked, as though education were something laughable. As though you had never heard the word before.

Well, laugh, then. Why not? After all, education is useless here. A man who has read Kant and Aristotle wipes the same stains off the same floor as a man who has read nothing at all. And if he dares to point out the difference, the educated man is the bigger fool, because he actually believed the world would care.

But let me tell you something, you who inspect floors at dawn: it is precisely because I am educated that I can see how petty this little power of yours really is. That you stand over me not because you are better, but because you are willing to pretend you are. You keep your hands clean while I dirty mine. You do not have to think. I do.

And so here we are: you, the inspector, the boss, secure in your small authority; me, the cleaner, secure only in the knowledge of my own absurdity. The others do not notice. They are happy enough to wipe and go home. But I — no, I am cursed to notice everything, to feel everything, to see through everything.

And so, yes, I was ready to resign. And perhaps I still am. But know this: if I do stay, it is not because of you, nor because I need this job so badly, though I do, but because it amuses me to watch you think you have won.

There is nothing more contemptible than to obey a petty tyrant out of necessity. But there is also nothing more human.

Yours unwillingly,

Samuel D. Keller

To: Mrs. Margaret Whitely

Subject: And Another Thing

Date: March 6, 2025

Madam,

Forgive the intrusion of yet another letter, though why I say “forgive” when I know you will not is beyond me. The truth is I could not sleep. That often happens to men who think too much and clean too little.

I realized after sending my last note that I had not quite finished saying what I needed to say. It always happens this way: I stew and mutter, and the words boil over later, too late. Well, better late than never.

I said, and still say, that your power is petty. Petty, but effective. And is that not the genius of it? That you can make a man of education, a man who once stood at a lectern quoting Aristotle, now stand before you, mop in hand, silent, shamed, afraid. A man who has read about virtue and freedom and human dignity, yet quivers like a dog when you scold him for missing a spot under the machine.

Why? Why do I quiver? Why do I stay? Because necessity is stronger than pride, and you know it. You count on it.

And yet you must also know, though you will never say it aloud, that I despise you for it. Not just you as a person — perhaps you are no worse than the rest — but you as a symbol of the whole miserable little order of things. The floors must be cleaned, and somebody must inspect them. But does it have to be you, and me?

Do you ever feel ridiculous, I wonder? Standing there in your little shoes, clipboard in hand, frowning at a stain? Do you ever think, even for a second, how absurd it all is? Or are you blissfully unaware, like the others?

It must be a kind of bliss, that ignorance. To never question, never see. To inspect a man’s work without seeing the man.

But I am not ignorant, and that is why I suffer.

And so tomorrow night, I will return. I will scrub, as I always do. You will inspect, as you always do. And nothing will change. Not yet. Not outwardly. But know this: every time you glance at me and see only another pair of hands, know that there is a mind behind them, a mind you cannot reach, and cannot bend, no matter how petty your power or how sharp your little notes.

And so: until the next inspection.

Samuel D. Keller

P.S. If you find this letter impertinent, good. It was meant to be.

To: Mrs. Margaret Whitely

Subject: You Will Never Read This

Date: March 9, 2025

Madam,

How strange, to address you as though you might read this, when I already know I will never send it. You will never see these words. You will never know what I thought of you as you stood there with your little note, telling me I had missed something again, your tone just sharp enough to sting, but not sharp enough to leave a mark anyone else would notice.

Oh, but I notice.

Every time you pass by with that clipboard of yours, something in me recoils, and something else in me smiles. Do you know why? Because I see you for what you are: a little queen of a little kingdom, ruling over a realm of dust and grease and tired men. And you think yourself grand. You think yourself in command.

But I know better. I see the absurdity of it all, the absurdity of you, and that knowledge is my secret revenge.

You think I fear you. And in a way, I do. I flinch when you scold me, I mumble apologies, I even consider quitting just to escape your gaze. But that is only the fear of a body, not of a mind. My mind sits in its corner, arms crossed, laughing at both of us.

You will never know how many times I have written this letter to you, in my head, on scraps of paper, in the air as I drag my mop across the floor. Every time you raise your voice, another version of this letter begins. Sometimes I taunt you more cruelly. Sometimes I pity you. Sometimes I imagine you reading this and realizing, with horror, that I see right through you.

And yet I never send it. Of course not. I am far too much of a coward for that. It is one thing to feel superior in my mind, it is another to risk whatever small scrap of dignity I still cling to by actually saying these things aloud.

And so you will go on inspecting, and I will go on scrubbing, and you will never know how much I loathe you, and how much I loathe myself for loathing you.

But sometimes, in the small hours, I imagine you reading this. I imagine the look on your face when you realize you have never really beaten me, not where it counts.

That is enough.

Yours, but only in the shallowest sense of the word,

Samuel D. Keller

To: Mrs. Margaret Whitely

Subject: An Apology (Of Sorts)

Date: March 12, 2025

Madam,

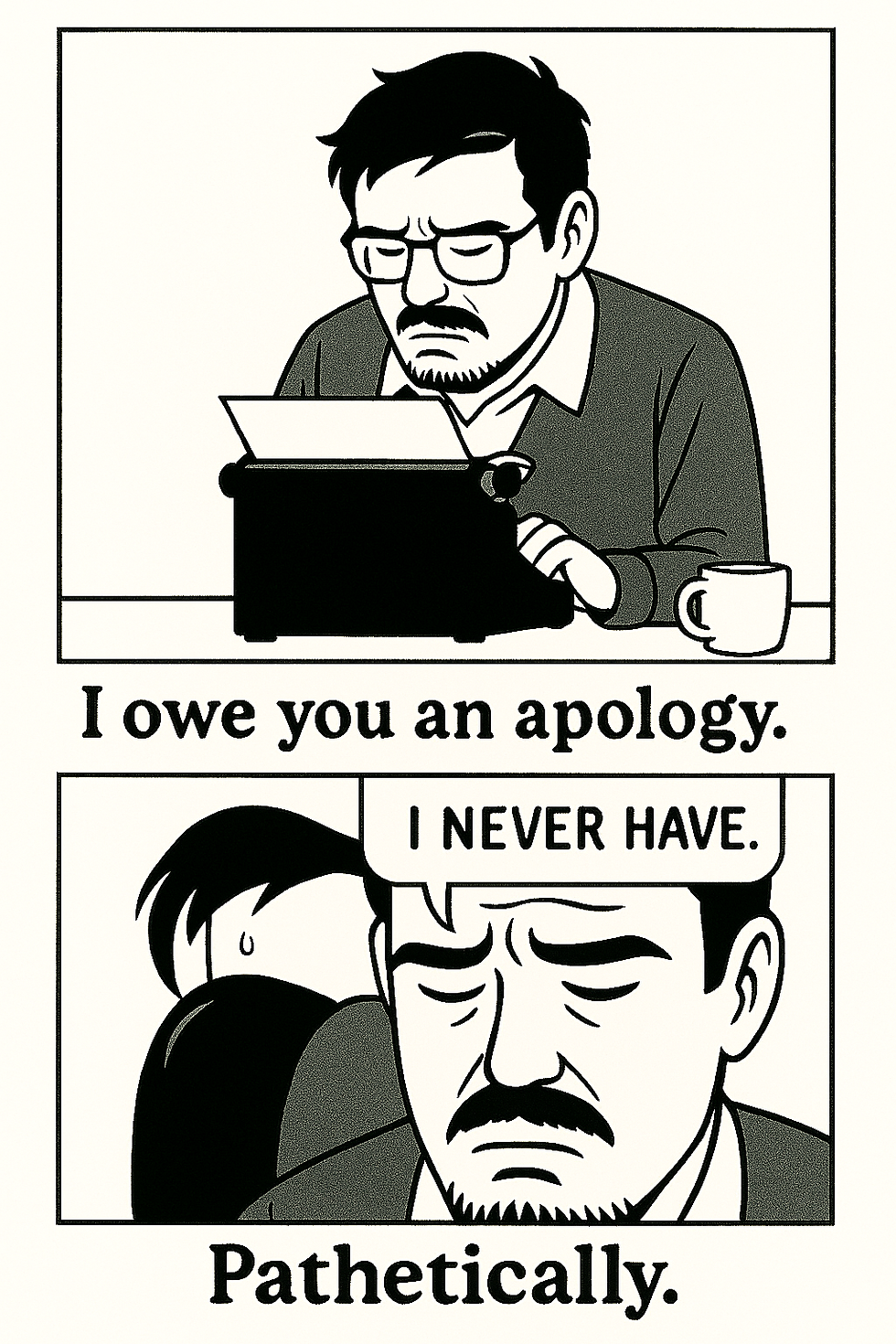

I owe you an apology. I should not have spoken to you the way I did. I should not have told you I was ready to resign. That was childish, dramatic, and, worst of all, dishonest. Because the truth is, of course, I am not ready to resign. I never was.

I do not have the courage. I never have. I like to imagine myself as a man of principle, a man of education, a man with a spine. But the reality is, I am spineless. And you knew it the whole time, did you not?

Oh yes, you knew. That is why you pressed me, cornered me. You could see in my eyes that I would never actually walk away. That no matter how high and mighty I pretend to be, I will always come crawling back to this miserable little job, because I need it.

You have won, and I know it. And what is worse, I know you will win again tomorrow, and the next day, and the next.

So yes, I apologize. Not because I respect you — if I am honest, I do not. Not because you deserve it — if I am honest, you do not. But because I have no choice. Because I am weak. Because this is what weak men do.

They grovel.

So here I am: groveling. I hope you are happy.

Pathetically,

Samuel D. Keller

P.S. Please feel free to keep this letter in my file as evidence of my utter, permanent defeat.